Acquisitions in Thrift Land

What to look for when evaluating whether a thrift is a potential takeout target

Greetings and welcome to another edition of Conversion Confidential! Awhile back, a reader commented (user generated content, yes!) that investing in small thrifts is investing in a hope and a prayer. By that he meant that relying on a bank to sell in order to get decent returns isn’t an investment strategy. At risk of putting words in his mouth, I believe he would say it is almost akin to the greater fool strategy where someone must come along and pay a higher price in order for the investment outcome to be a desirable one. There are elements to that concern which are true, but is an acquirer of a small bank actually a fool? And what has occurred historically, is there anything that can be done to improve the odds of investing in a thrift where a takeout will ultimately occur?

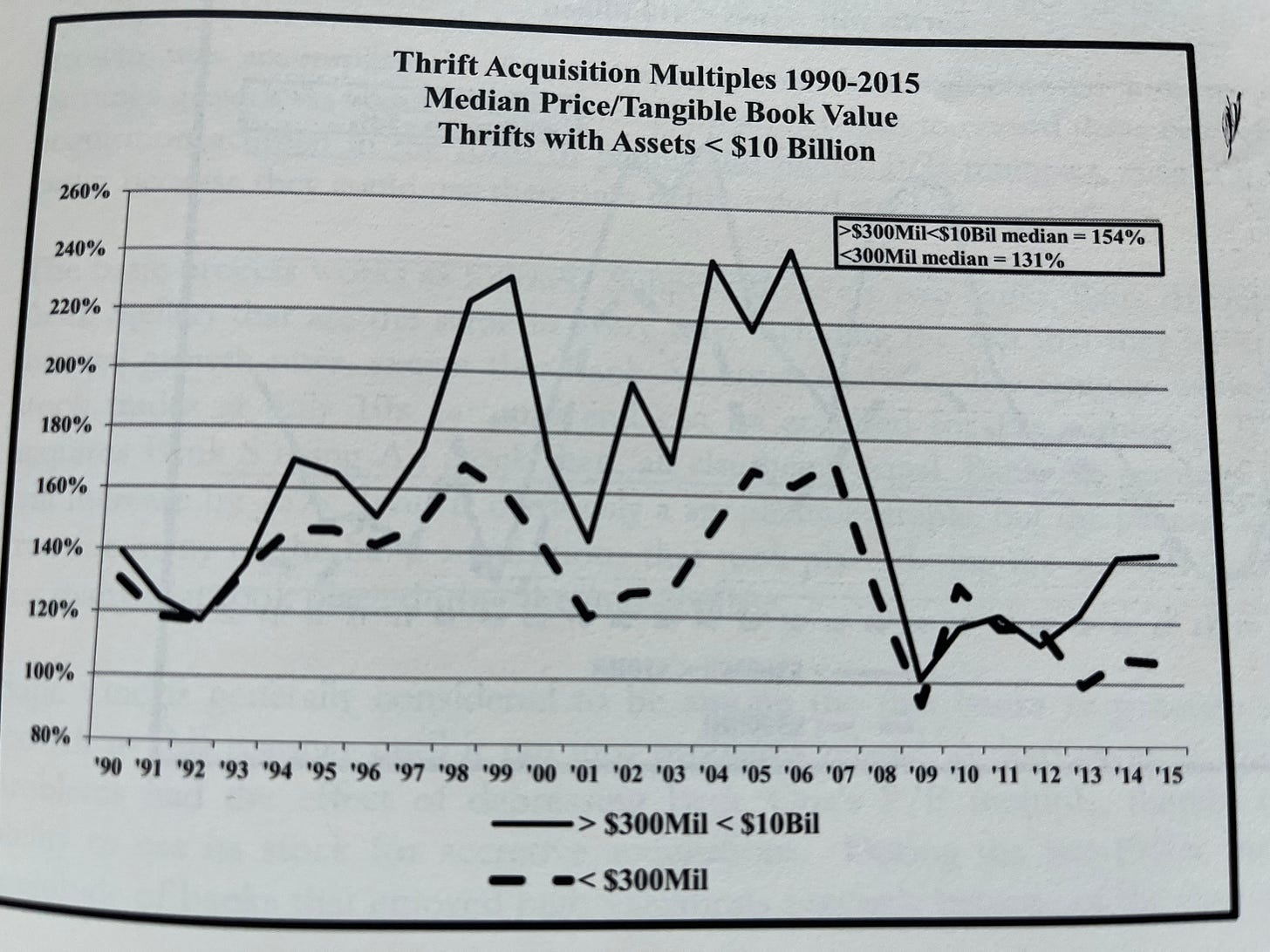

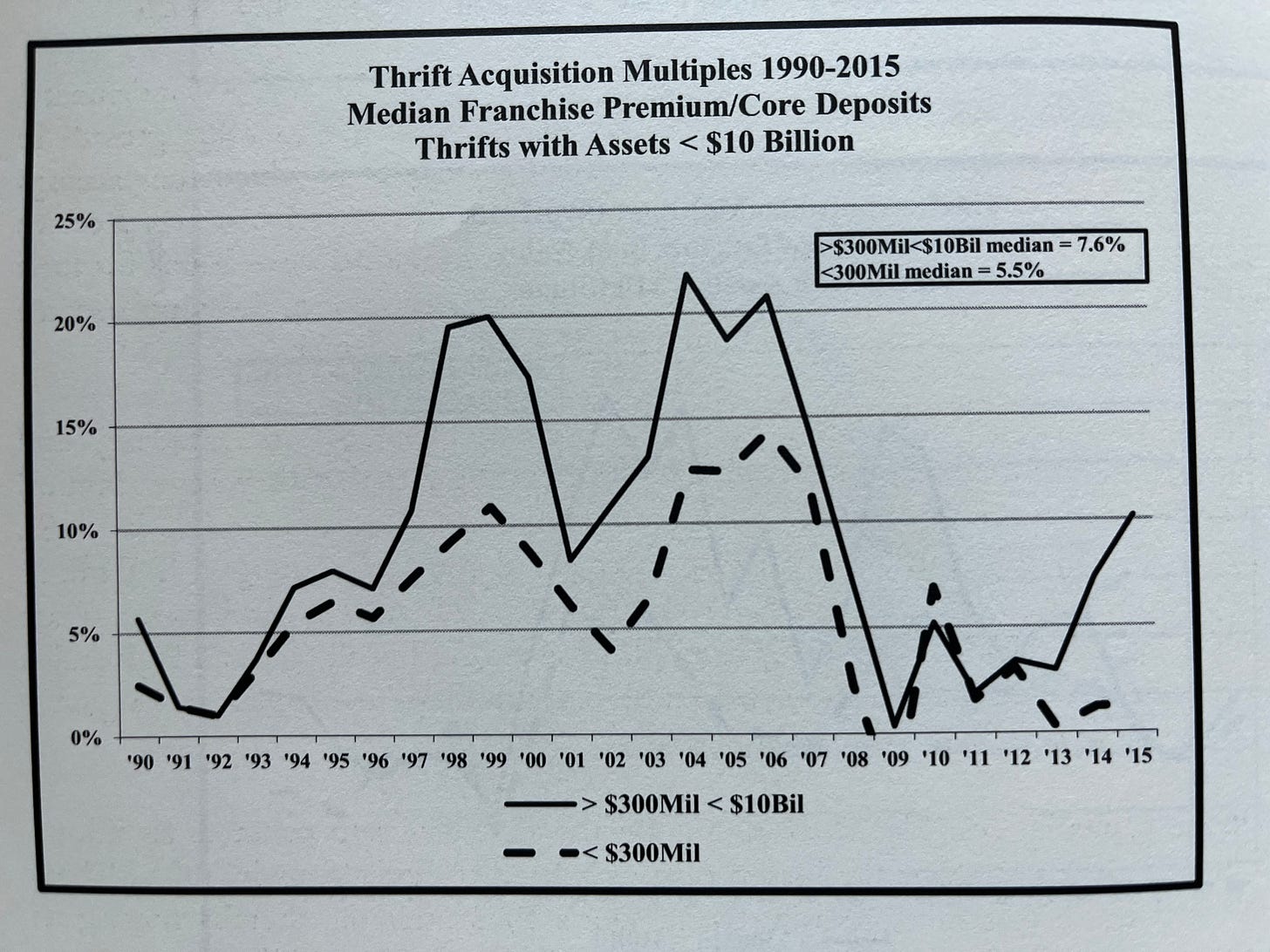

In Jim Royal’s book, The Zen of Thrift Conversions, he cites a 2016 report by investment bank Piper Jaffrey that concludes since 1982, ~70% of demutualized banks that reached their third full year as a public entity have been acquired. The report also suggests these thrifts came to market at an average valuation of 75% of TBV and were taken out at an average multiple of about 140% of TBV, in a median time frame of five years. For a more detailed view of thrift acquisition statistics, see the images I have included on takeout values at the end of the post.

While the above data set from the Federal Reserve was discontinued in 3Q20, it’s not difficult to see that there have never been fewer banks than there are today. We also know that the US has the highest number of banks per capita in the world and that consolidation has been, and continues to be, a major theme in the industry as a result. To me, this sets a decent historical precedent that the odds of a transaction in banking are already in your favor.

Why Do Acquisitions Occur?

So why do informed bankers buy others banks anyway? Hopefully it starts with a desire and realistic ability to increase the franchise value of the acquirer. Numerous rationales exist, but I’ve listed the main ones below:

Achieving scale - when two banks merge, there are redundant operating costs in senior management, accounting, finance, operations etc. (i.e. non-interest expenses) that can be eliminated from the business. This enables an acquirer to spread their existing cost base over a larger customer/asset base with little incremental expense, immediately improving their long-term economics. Estimates of the acquiree’s non-interest expenses that can be eliminated in a merger seem to range from 20-40%. Small target banks may also be paying too high a rate on deposits which can be another source of savvy acquirer’s cost savings. Lastly, new products and services that the acquired bank didn’t offer can be cross sold to new customers of the acquirer (what’s known as revenue synergies). The most reliable of these all however is the reduction in operating expenses.

Market Expansion - an acquisition may strengthen the acquirer’s local market share, remove a competitor, and/or give them access to a larger geographical or customer footprint.

Risk reduction - by merging with another bank, the loan book of the acquirer may be diversified away from one particular type of lending.

Acquisitions likely fail for three primary reasons. First, the acquirer may overpay, thereby transferring too much of the value of the deal to the shareholders of the selling institution. Watch out for an acquisition that may be advantageous to insiders but comes at the expense of shareholders. After all, there is a strong link between bank asset size and executive compensation so the principal-agent problem remains alive and well.

Similarly, mistakes may also be made in due diligence of the loan portfolio. If an acquirer has to remedy numerous credit issues they didn’t anticipate in initial underwriting, the expected cost savings of the deal may go out the window. There can also be integration issues with core banking systems or any other operating systems that either bank relies on and must consolidate. Lastly, and perhaps most importantly, there can also be a clash of cultures between the two different banks. This can lead to devastating turnover in key personnel, customers, or both.

Selling a Bank and Identifying Acquisition Targets

Similar to the reasons for acquiring another bank, hopefully the ultimate rationale for selling a bank is to maximize shareholder value and take advantage of a strong offer. It would be naïve to suggest that’s the only or even dominant motivation however. Selling out may also provide an opportunity for management to cash out (incentives!), remedy a succession issue, or reflect an answer to the common challenges for small banks such as limited growth opportunities, rising regulatory pressure, and/or increasing costs to compete.

A number of clues may exist that demonstrate a bank’s willingness to sell itself and they tend to start at the top with leadership. Is the CEO and/or board of directors nearing retirement age? Have they been at the bank for a long time and built up a meaningful ownership stake? If the answer to either of these is yes, you’re probably increasing your odds of an eventual takeout. David Moore notes in his book, Analyzing and Investing in Community Banks however that industry consolidation and fewer de-novo banks coming to market has also limited the senior positions available at other banks. The implication is that there may not be a job waiting for the management team once their bank is acquired. This may result in insiders becoming extremely reluctant to sell so as to try to preserve their position as long as possible.

Another relevant question to ask is whether the CEO (or a major shareholder such as an activist) has a history of fixing up, or selling banks previously. Have they taken other shareholder friendly actions such as repurchasing shares? History is never a perfect guide but assessing how someone has behaved in the past, does give you a decent sense of how they might be likely to behave and perform in the future.

Lastly, are there a declining number of potential acquirers in the local market? Nobody wants to be the last game in town (especially if they are a subscale operation) as that would mean there are fewer bidders for an exit opportunity which is detrimental to receiving a good selling price.

Attractive Acquisition Candidates

Here are a few of the redeeming qualities of a bank or thrift which increases their attractiveness as a takeout candidate:

Strong deposit franchise - a high mix of non-interest bearing deposits or core deposits combined with a low percentage of CDs/brokered deposits is very desirable. A strong deposit base is difficult and time consuming to replicate so acquirers are willing to pay higher takeout premiums for them. Strong deposit franchises will also only be of more value in an environment where interest rates are higher. All else equal, potential suitors also prefer larger deposit balances per branch because fixed costs can be spread over the higher deposit base.

Healthy market/sensible proximity - the ideal target is also located within, or is a natural extension of the acquirer’s home market and situated in growing regions and/or upscale areas. Community banking is by definition impacted by the local economy. Population, job, and income growth are all desirable from the perspective of an acquirer because they increase demand for banking products/services, as is a wealthier customer base. Higher income customers tend to use more banking products/services (cross-sell opportunities), maintain higher deposit balances and may be less impacted by an economic downturn, therefore representing less of a risk to credit quality. A strong market is also likely to have more banks in the area, which likely means more competition, but may also benefit sellers in the form of more potential suitors.

Elevated operating expenses - this one may seem counterintuitive, but remember, when a subscale thrift operates independently they tend to chew up a lot of their income on non-interest expenses. From the perspective of an acquirer however, these are costs that can be eliminated and makes the target more desirable, not less.

Anything that represents the opposite of the features listed above detracts from the acquisition value. High-cost/low-quality deposit bases, subscale/rundown branch networks (although there is also a potential opportunity to close them), undesirable geographic footprints, and extremely weak (negative) earnings or asset quality issues all lower takeout premiums. Management and directors without “skin in the game” or who have proven themselves unfriendly to shareholders should also be viewed with great skepticism. They may have no interest in selling the bank because it would be to their own detriment. Why lose the compensation, perks, influence, prestige and reputation of the job when there might not be another available bank to jump ship to?

As promised, I have included two charts which provide a bit more granularity on historical thrift acquisition takeout values. One is based on multiples of TBV and the other is based on core deposit premiums. It’s not a coincidence these are my preferred method of valuing thrifts. The charts are a few years old at this point, but provide a clear enough picture all the same. You can see that acquisition multiples have compressed in the past decade, likely the results of lower interest rates and profitability in the industry. Both images are from David Moore’s Analyzing and Investing in Community Banks and his data source is SNL, now apart of S&P’s Market Intelligence Platform.

Of course, if doing a full comparable analysis for a potential acquisition, one should take into account differences in, and make adjustments to the subject bank in areas such as profitability, the deposit franchise, the bank’s market and customer base, asset quality, and capital levels. Comps should be ideally narrowed down to other thrifts/banks with a recent sale in the past couple years, that are of similar asset size and from the same geographic region. The fairness opinion in the proxy statements of a potential merger will usually do a lot of the heavy lifting for you, but it’s worth making sure they are relevant comparisons. Lastly, don’t mix bank and thrifts as valuations for the former will be higher than the latter.

Last, but not least, I’d like to leave you all with a link to M&T’s 2021 shareholder letter. M&T is a large, well run bank out of Buffalo, NY that has looked to M&A activity to build itself over the years. M&T is currently working on a merger with People’s United Financial. The letter has some nice commentary on various considerations in their merger such as integration efforts, as well as deposit market share. Despite discussing banks that are much larger than traditional thrifts, I think it will serve as a nice supplement to today’s issue. That’s all for this week folks. Thanks for reading!

Banks love buying banks! Who knew!?

Excellent summary. The premium is basically capitalized cost savings, as you say.

Your two valuation charts share the same Achilles heel of trying to reduce a three variable calculation to two variables. Essentially, the buyer is buying the net worth $ for $ and then paying a premium for the deposits. Measuring either P/BV or P/Deposits isn't terribly accurate because a thrift with 5% equity/assets and a thrift with 10% equity/assets will show very different P/BV even if they get the same deposit premium. Really, you want to calculate (P-BV)/Deposits for the best measure.