Anatomy of the Standard Thrift Conversion

A look at the internal workings of a mutual-to-stock conversion

Greetings! This week I’d like to walk through the fundamentals of a thrift conversion and shed some light on the unique structure/process for those who may be less familiar. Then next weekend, I’ll be back with a write-up of a newly converted thrift. Hopefully, the practical application of a real-time case study will make this post come into clearer focus for those new to thrift conversions.

For starters, thrift conversions are typically labeled a “standard conversion”, “first-step”, or “second-step” conversion. In this post, I’ll walk through the basics of the standard conversion (aka single-step conversion) process. First and second step conversions, along with the associated mutual holding companies (MHCs) they produce, will be addressed in a future post.

The standard conversion process is relatively straightforward, but starts with a unique organizational structure, the mutual bank. What is a mutual bank you ask? Well, it means that the institution is technically owned by its depositors as opposed to shareholders like in a typical public company. These depositors, or members, do not have voting rights in its operations nor do they receive dividends. Mutual banks also aren’t allowed to raise outside capital so their growth is a function of whatever equity they began with and their retained earnings. Mutual banks exist for the purpose of providing basic, low-cost loans (predominantly residential mortgages, or commercial real estate mortgages) to the members of the local community, not unlike a credit union.

Now, before we go any further, a quick note on nomenclature because I can envision readers new to the space getting confused with the various terms. Put simply, mutual banks are often referred to as thrifts or savings & loan institutions (S&Ls). While there were some philosophical and functional differences between each of them in the past, for all intents and purposes, they can be thought of as synonyms since financial deregulation has blurred the distinctions between them. Technically, I believe the term “thrift” would be the most encompassing, but that’s neither here nor there.

The process by which a mutual bank becomes a publicly traded stock listed on an exchange is known as a mutual-to-stock conversion. You may have also heard it referred to as a demutualization or my preferred term, the thrift conversion. This process of a thrift converting to a public company is where things get interesting.

Over time, a profitable thrift will build up equity from its net earnings and depositors have a claim on this equity, but only if management ever decides to convert the mutual bank to stock ownership via an initial public offering (IPO). Ownership interests of the post-conversion thrift are first offered to these depositors as well as company insiders. If not enough interest is gathered through them in the offering, the IPO may be opened to the wider local community or other investors.

But unlike in the traditional IPO where there are shares exchanging ownership hands and insiders are selling to less knowledgeable buyers, a thrift conversion has none of this. Any proceeds raised from the IPO are simply added to the existing equity of the thrift, which all shareholders then have a claim to after the conversion is completed. This is why our good friend Peter Lynch enjoyed the thrift conversion space so much.

A normal company has founders, early investors, and venture capitalists, all of whom claim a share of the proceeds from a stock sale when the company goes public. But a mutual savings bank has only depositors. There are no sellers to compensate. Officers and directors may get free stock, as we've noted, but all the cash that's raised in the offering, minus the underwriting fee, is returned to the company till.

- Peter Lynch

In a traditional IPO, the selling insiders largely want as high of a valuation as possible (with the understanding to leave some of the “first day pop” on the table for investment banks who help put the deal together) in order to maximize the value of their holdings. The pricing in a thrift conversion IPO works differently however, largely due to insider incentives. Remember, while the depositors of the thrift have a claim to the equity of the thrift, they do not actually have any historical investment, or cost basis in it. This means that when it comes to pricing the shares that will give them true ownership rights in a cash rich, post-conversion public bank, they would like to purchase shares at as cheap a valuation as possible. It is simply in their best interests and we all know (or should know) the power of incentives. While there is more to it than that (such as an appraiser helping management price the subscription), the end result is largely the same. To reiterate, the proceeds collected from the IPO subscription are transferred almost entirely (minus standard fees) to the thrift itself (not to insiders), adding to its net worth. Those who participated in the offering now own the pre-existing equity of the bank plus the total proceeds raised in the offering. In other words, they are essentially repurchasing their own capital and receiving the equity of the bank that they are entitled to as a depositor for free.

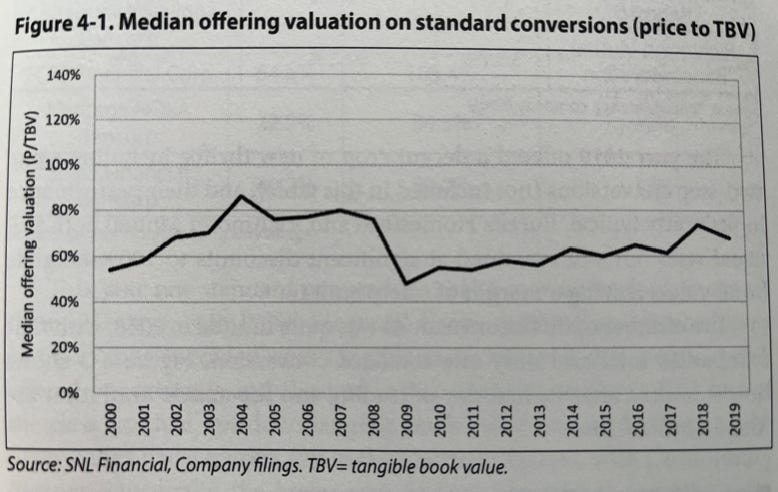

This quirky structure means that a thrift conversion will essentially always be underpriced unless the converting bank is insolvent. Investors who come in at the subscription offering benefit because the thrift is typically priced at 60-70% of pro-forma tangible book value (TBV), and sometimes less. A fine line exists between pricing the bank at too low a valuation and thus raising less capital, or pricing at a higher valuation and raising more capital. The former is in the interests of the bank as more shares are sold while the latter benefits participants of the conversion as fewer shares are sold. Higher or lower demand from depositors, insiders, and investors will drive the final amounts of capital raised and at which valuations. The below chart is from Jim Royal’s, The Zen of Thrift Conversions and displays the historical phenomena of thrift conversions coming to market at noticeable discounts to TBV.

Now I know book value isn’t viewed as the indicator of intrinsic value it once was (thinking with which I agree is correct for most companies today), but I still think it’s meaningful for financial companies. If a bank trades below its net equity value, investors are usually signaling the business will destroy value, permanently remain unprofitable, or worse, go under. However, that’s not the typical outcome with over-capitalized thrifts.

As a result, a minimum of tangible book value is where many banks will ultimately trade or be acquired at. Anything less implies the bank is worth more dead than alive and the upside could be captured in a liquidation. Because many thrift conversion IPOs are priced at a material discount to TBV (the larger the discount the better for buyers in the offering), share price increases of 20-30% are not uncommon on the first day of trading post the conversion. It is a recognition by the market of the value that exists within the thrift’s original equity. Meanwhile, longer term, the best thrifts tend to drift towards a valuation commensurate with a takeout value well over 1x TBV. The key is finding thrifts with higher quality characteristics and/or management teams willing to do “the right things”, or what I’ve referred to in other posts as executing the thrift conversion playbook.

So to sum up and make this more practical, how does one invest in a standard thrift conversion? I think there are two primary methods:

Open accounts in the remaining mutual banks around the country and place deposits with them in the hopes they eventually convert to stock ownership. You would have a right as a depositor to subscribe in the offering at the favorable pricing alongside insiders under most circumstances.

Invest in thrift conversions after they come public (post their initial pop), hunting for those that exhibit characteristics of higher class thrifts/management teams while remaining vigilant on the price paid and future value in order to maximize your returns.

The problem with option number one is you don’t know when the management team of a thrift will convert to public ownership (not to mention you could be opening dozens or even hundreds of random accounts). It could be tomorrow, many years from now, or never. Naturally, it becomes a question of opportunity costs. An investor needs to think of it from a time value of money perspective and since I don’t know how to assess which thrifts might convert in relatively short order, I have personally avoided this strategy. I have also heard that it is more difficult to find a mutual bank willing to take deposits as a non-local resident than it used to be. However, assuming you are able to and can eventually participate in a conversion with a significant sum of capital, the results could be incredibly rewarding.

I am more intrigued with option number two above. In my opinion, some of the timing uncertainty has been removed by knowing that a good majority of thrifts are ultimately bought out. If you can align yourselves with management who also think along these lines and/or may be nearing retirement age, you’re likely increasing the odds in of a favorable outcome.

Well, that’s it for this week. I’ll be back with a practical example next time. Thanks for reading!

Just came across this substack and I have to say I’m super impressed! Best wishes for all future endeavors with your thrift investing my friend.

In terms of strategy #1, it seems like a classic Buffett Moody’s Manual play - whoever that actually takes the time to comb through it all will likely pick up gems in broad daylight. I’m going to call each mutual bank and inquire them about opening accounts. These places seem like a good place to stash long term savings, plus they are FDIC insured.

Would love to follow more on #2 - I’m going to use bankinvestor to keep track.