Seth Klarman on Thrift Conversions

Another investing legend weighs in on thrifts, and what we can learn from it

Aloha and welcome to another issue of Conversion Confidential! I’m in Hawaii for the next eight days so I’m going to relax and attempt to keep my writeups a bit more concise. Don’t worry though, I’m working on another thrift conversion in the background, and will post on it in the coming weeks. However, it requires more time and effort than I’m willing to sacrifice on a Saturday in Oahu.

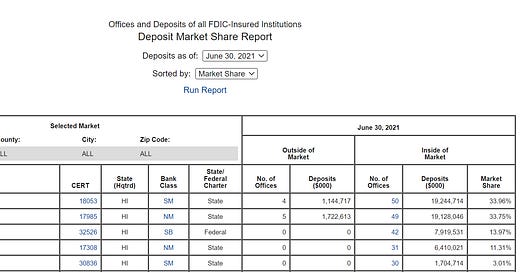

Now since I’m in Hawaii, I figured I’d investigate whether I could open a savings account at a local thrift. The idea would be to participate in the subscription offering if it ever converts to stock ownership someday. With that in mind, I headed over to the FDIC list of mutual institutions. Sadly, there are no mutual banks in Hawaii! So much for that idea. It’s also no wonder the few Hawaiian banks that are here tend to earn returns on assets (ROA) of 1% plus pretty consistently. Less competition is a nice feature for any industry and in Hawaii, the top five banks on the islands account for a whopping 95% of total deposits!

Okay, with that, let’s move on to my intended subject for the week.

Analyzing Thrift Conversions Through Klarman’s Eyes

In Margin of Safety: Risk-Averse Value Investing Strategies for the Thoughtful Investor, Seth Klarman dedicates a brief chapter to thrift conversions and even highlights one, Jamaica Savings Bank (JSB) as a mini case study. Just like Peter Lynch, Klarman found thrift conversions to be a good source for investments with a favorable risk/reward ratio, or what I like to call asymmetry. Here’s a number of highlights from the chapter on thrifts:

Since 1983 the conversion of hundreds of mutual thrift institutions to stock ownership has created numerous opportunities for value investors. Negative publicity coupled with the economics of thrift conversions served to unduly depress the share prices of many thrifts.

By the 1980s, however, much of the thrift industry was hemorrhaging money. Financial deregulation had adversely impacted most thrifts in that the interest rates paid on deposit liabilities were suddenly allowed to fluctuate with market interest rates, while most thrift assets, in the form of home mortgage loans, bore fixed interest rates. For many thrifts, the cost of funds soon rose above the yield on their assets, resulting in a negative interest rate spread.

So long as the thrift has positive business value before the conversion, the arithmetic of a thrift conversion is highly favorable to investors. Unlike any other type of initial public offering, in a thrift conversion there are no prior shareholders; all of the shares in the institution that will be outstanding after the offering are issued and sold on the conversion. The conversion proceeds are added to the preexisting capital of the institution, which is indirectly handed to the new shareholders without cost to them. In a real sense, investors in a thrift conversion are buying their own money and getting the preexisting capital in the thrift for free.

There is another unique aspect to thrift conversions. Unlike many IPOs, in which insiders who bought at very low prices sell some of their shares at the time of the offering, in a thrift conversion insiders virtually always buy shares alongside the public and at the same price. Thrift conversions are the only investment in which both the volume and price of insider buying is fully disclosed ahead of time and in which the public has the opportunity to join the insiders on equal terms.

Many thrifts, of course, are worth less than their stated book value, and some are insolvent. Funds raised on the conversion of such institutions would pay to resolve preexisting problems rather than add to preexisting value.

No major Wall Street house was able to get a handle on all of the many hundreds of converted thrifts, and few institutional investors even made the effort. As a result, shares in new thrift conversions were frequently issued at an appreciable discount to the valuation multiples of other publicly traded thrifts in order to get investors to notice and buy them.

Fundamental investment analysis applies to thrifts as it would to other businesses. Thrifts incurring high risks, such as expanding into exotic areas of lending or venturing far from home, should simply be avoided as unanalyzable.

Thrifts speculating in newfangled instruments such as junk bonds or complex mortgage securities (those based on interest or principal only, for example) should be shunned for the same reason. A simple rule applies: if you don't quickly comprehend what a company is doing, then management probably doesn't either (emphasis mine).

While all businesses should be valued conservatively, conservatism is even more important in the case of highly leveraged financial institutions where operating risks are magnified by the capital structure. In evaluating such thrifts, book value is usually a low estimate of private market value; most thrift takeovers occur at a premium to book value. Investors should adjust book value upward, however, to reflect understated assets, such as appreciated investment securities, below-market leases, real estate carried below current worth, and the value of a stable, low-cost deposit base.

Similarly book value should be adjusted downward to reflect balance sheet intangibles, bad loans, and investments worth less than cost.

As part of the fundamental analysis of a thrift, its earnings should be adjusted for such nonrecurring items as securities gains and losses, real estate gains and losses, branch sales, real estate development profits, and accounting changes.

Thrifts with low overhead costs are preferable to high-cost institutions both because they are more profitable and because they enjoy greater flexibility in times of narrow interest rate spreads.

There are many risks in any thrift investment, including asset quality, interest rate volatility, management discretion, and the unpredictable actions of competitors. Investors, as always, must analyze each potential thrift conversion investment not as an instance of an often attractive market niche but individually on its merits.

- Seth Klarman, Margin of Safety

Specifically on Jamaica Savings Bank, Klarman noted the bank was offered at 47% of book value and a 10x price/earnings multiple. While the valuation on book value is comparable to a conversion price you might see today, the low price/earnings multiple tells me JSB was probably a lot more profitable than many thrifts that convert these days.

Klarman also noted JSB had a tangible capital to total assets (aka the TCE ratio) of 13.5% pre-conversion, which was one of the highest ratios in the country at the time. Two thirds of its assets were also invested in Treasuries or other federal securities/cash. This required just 30% to be invested in loans, essentially all of which were lower risk residential mortgages. As Klarman wrote, “JSB was in a class by itself: liquid, well capitalized, and without material business risk.”

Klarman was also enthusiastic regarding JSB’s ability to repurchase its own shares. With half of the offering proceeds retained at the bank holding company, he figured the bank might be able to cannibalize a significant share of the company at a low valuation. And if not, the effect of a substantial buyback program would likely mount pressure on the share price to rise.

Investors in JSB stood to profit in several ways. The earnings appeared likely to grow as the excess capital was deployed. Book value would also grow due to earnings retention. Management moreover was dedicated to enhancing shareholder value through an aggressive stock repurchase program; this would increase both earnings and book value per share. Indeed, management purchased a significant amount of stock in the IPO for itself. As it turned out, the first trade in JSB took place at a 30 percent premium to the offering price, and the shares remained at a premium even when the stock market slumped later in the year.

- Seth Klarman, Margin of Safety

It’s possible the heyday for thrift conversion investing has passed with current opportunities not quite as compelling as those Klarman found in the 1980s and 1990s. However, my takeaway from his writing is to remain focused on the fundamentals and let the opportunities come to you by seeking:

High capital/low leverage

Operational simplicity

Conservative lending

Sound asset quality

Aligned management

Share repurchases

Low valuation

That’s it for this week. Mahalo!